|

The birds and flowers and frogs are mostly figured out on the tepuis, but the little stuff is where the new stuff is.

0 Comments

One of my trips was to the Chimantá tepui in Venezuela (click the VZ category for more blog pics from there). And one of my photos is of a Rufus-collared sparrow on that tepui.

This sparrow is quite common in places across much of South America and even up into Mexico. I first saw it on my travels in the Dominican Republic some 15 years ago, and have seen it in Peru as well. But on the VZ tepuis, it seems to be a relic species with no suitable habitat connecting it to any other population of the birds. Phone Darwin, as it seems like a brew for a new species to be born in the next maybe 1,000 years? We were far into the cave, and doing a lot of science, with the plan to take some nice photos of the passages on the way out. I left the high ledge we were on a bit early to set up some photo shots. But while sitting on a big rock down at the stream with my camera and tripod in place, waiting for Don and Joyce, I noticed that the water was rising. Not so much, but it was rising. By the time they got back down, the cave stream had risen about a foot and it was no longer about getting photos but getting out quickly before we were trapped by high water. We raced downstream, and had a bit of fun at what were short waterfalls earlier. Wearing 18-inch high waterproof boots worked well until now, as they got filled with water descending the 2-meter high falls. But without any major trouble, we made it to the entrance. Don looks pretty small in this picture, looking out toward the entrance. But just a few hours later the water was up to almost where he is standing. It is good we got out when we did.

The aquatic cricket, Hydrolutos breweri...presented in three pics. This cricket has been properly noted as a unique species here:

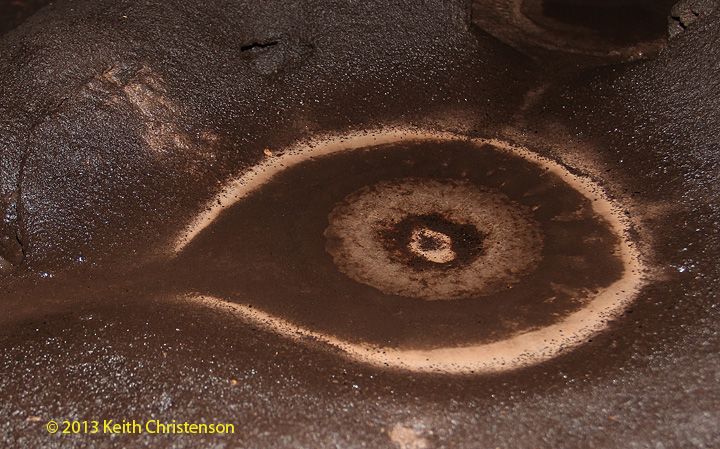

http://cabinetoffreshwatercuriosities.com/2011/09/06/the-venezuelan-cave-cricket-hydrolutos-breweri/ I found these drip pools on top of little sediment mounds to be quite interesting. And am unsure exactly how these mounds got there.

There aren't so many flat spots to camp. Well, to be truthful there aren't any flat spots. But this big rock in the entrance to Charles Brewer Cave was best. It wasn't flat, and obviously hard as rock, but made for our multi-day camp for work in the cave. This cave has had maybe a dozen visits by cavers. But a number of chairs and similar stuff have been stashed there to make things more comfortable for future explorers. Here is coffee in the morning.

Zuna Cave was not so far from our surface camp, and not a killer hike (some places on the Tepuis of Venezuela are ridiculously difficult to traverse). So here is a picture of Don McFarlane on the rope we used to get to the cave. The pic is taken roughly looking straight up. It is a 40-meter drop, but I was on a giant rock so only 30 meters of rope are shown. And the ever lovely Joyce Lundberg rappelling down toward the bolt that made the rest of the rappel a free drop. The cave had quite a lot of these giant mushroom-like formations. And since the rock is sandstone, quite remarkable. Limestone caves can have an abundance of calcite formations, but sandstone caves do not typically have formations. This bit is part of why we were there. The cave is a stream cave, but water levels were way down when we visited. Even so, the one big room in the cave had a shower of water coming from the ceiling. But it was, in general not that wet.

|

AuthorKeith Christenson - Wildlife Biologist Categories

All

Author

Keith Christenson Wildlife Biologist Archives

September 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed